Responsible business conduct (RBC) is here to stay. There is a clear trend towards more binding RBC measures. Some countries have introduced thematic or sectoral due diligence legislation for specific RBC themes, such as forced labour and exploitation (including child labour) or for specific sectors (e.g. timber and minerals). Examples include the UK Modern Slavery Act (2015), the EU Timber Regulation (2010) and the US Dodd-Frank Act (2010). Recently, we have also seen the introduction of due diligence legislation with a broad scope that cuts across themes and sectors. France, for instance, introduced such legislation in 2017. In April 2020 the EU Commissioner for Justice (EC), Didier Reynders, announced a legislative initiative for sustainable corporate governance, including a corporate due diligence duty that should entail liability and enforcement mechanisms, as well as provide access to remedies for victims.

The key principle underlying international norms for RBC[1] is that businesses should identify risks in their international supply chains, take action to prevent or mitigate these risks, and communicate about their efforts in this regard. This is referred to as ‘due diligence’, which is concerned with the risk of human rights violations, such as forced labour and exploitation, as well as the risk of environmental damage.

Context

In line with the coalition agreement of 2017, the Dutch cabinet has evaluated its RBC policy and decided to take a step forward, by implementing new measures and strengthening existing ones. This blog post will explore the challenges and possibilities of the new Dutch RBC policy and will focus on the open questions regarding the building blocks for a due diligence obligation.

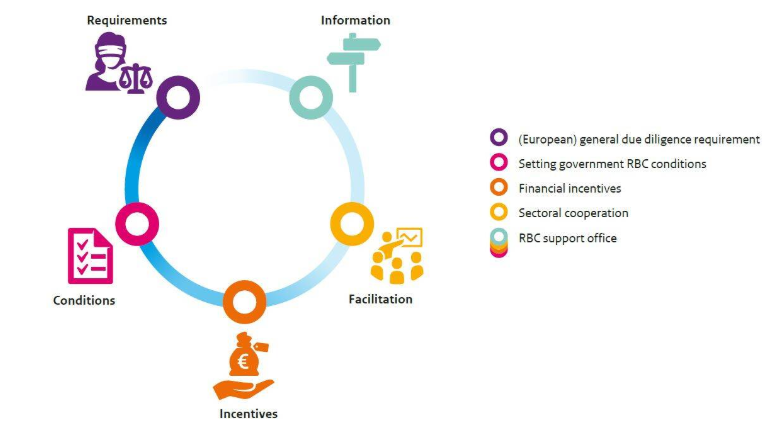

Last October, the Dutch government presented the main outline of new RBC policy. The cabinet agreed on a mix consisting of mutually reinforcing measures which together should lead to an effective change in behaviour among the target group (i.e. businesses, which are divided according to their progress on RBC into the leading pack, the peloton (i.e. main group) and the laggards). This policy mix allows for a response tailored to specific circumstances, and for measures that impose obligations, set the right conditions, and incentivize, facilitate and inform (a so-called ‘continuum’ in which the various tactics the government can use with policy instruments are represented, see: figure 1). This policy mix combines new instruments with existing ones. Existing instruments will be improved and reinforced on the basis of the evaluations of RBC policy.

Figure one: A Smart Mix of Policy Measures

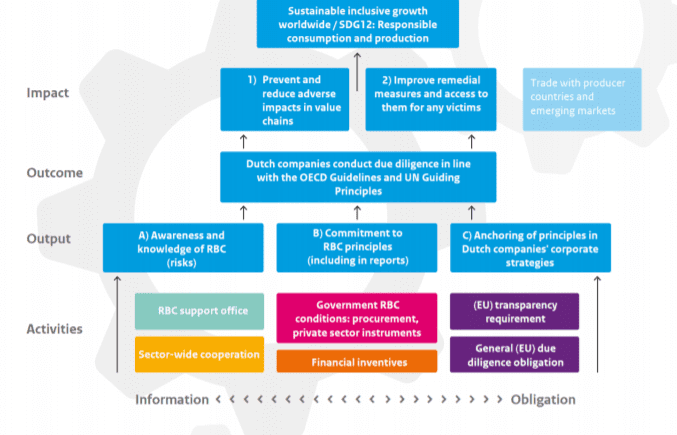

The Dutch government has developed a preliminary theory of change to gain insight into progress towards, and achievement of, the RBC policy goals. The measures in the smart mix must increase awareness and knowledge of RBC (risks), commitments to RBC principles (including in reports) and anchor principles in Dutch companies’ corporate strategies. The result of the smart mix should be that companies conduct due diligence in line with the international frameworks. This will prevent or reduce adverse impacts in value chains and also improve victims’ access to remedies (see: figure 2).

Figure 2: Theory of Change

A key element of the new smart mix is a general due diligence obligation. The effect of this mandatory element will mainly be to spur laggards into action, by obliging them to observe the principles of RBC.

The Dutch government is of the opinion that a due diligence obligation should preferably be implemented at the EU level. A European approach makes for a greater impact in the supply chain and ensures a level playing field. At the same time – with the adoption of the Child Labour (Duty of Care) Act – the Netherlands has assumed a responsibility of its own. Even though some issues concerning the organisation of oversight and the scope and the requirements for companies remain open, the Dutch government has made progress in the elaboration of the building blocks of due diligence legislation. Questions of this kind overlap precisely with a general due diligence obligation, regardless of whether it is introduced at the EU or national level. Building on the insights gained from the policy evaluation and exploration of policy options, the Dutch government is working out these aspects in more detail and is focusing primarily on exerting influence on EU policy making.

On top of this mandatory element, the Dutch government will also implement and strengthen several additional and existing instruments. These would include: a pilot regarding responsible public procurement; an RBC support office for businesses; and financial incentives and sector-wide cooperation. The idea of the public procurement pilot is to make Dutch government purchasing more in line with its policy under the motto “practise what you preach”. The support office will help Dutch companies with their possible questions regarding the implementation of the new due diligence standards. The support office must provide services in a complete and comprehensive manner and help limit the regulatory burden on businesses. The Dutch government has developed financial incentives to encourage companies in the leading group and the peloton to implement the OECD Guidelines, such as the Fund against Child Labour and the Fund for Responsible Business. The government will continue to encourage sectoral initiatives and sectoral cooperation aimed at conducting due diligence in line with the OECD Guidelines and/or at achieving impact on specific themes or supply chains.

Working out due diligence legislation in more detail: considerations

In the next part of this blog we will go deeper into the various aspects that need to be worked out for a due diligence obligation. As previously stated, there remain some questions about the scope of the obligation, the requirements for companies and the organisation of oversight and sanctions. What are the challenges in the transition from soft law (a voluntary approach) towards hard law (binding measures)?

Scope

Multiple variations are possible when deciding on the scope of new legislation. On the one hand, there are voices that are advocating for a due diligence obligation for all companies, regardless of their size. On the other hand, questions have been raised about the regulatory burden for companies, as well as governments, and the proportionality of such a broad scope. At the moment, the Dutch government is carrying out research into the regulatory burden of due diligence on companies. Could a possible solution be to have a cut-off at a certain company size or to exclude smaller companies from certain due diligence obligations? Or could it be an option to impose an obligation on companies that operate in so-called high risk sectors to increase the effectiveness and impact of the obligation? When deciding on the scope, it is important to take into account regulatory burden, proportionality and effectiveness.

Requirements for companies

In the new Dutch RBC policy the government is striving towards legislation that includes all six steps of the due diligence process as laid down in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. It is still an open question how this process can be best enshrined in the law. On the one hand, the dynamic nature of the OECD Guidelines enables companies to be flexible in how they address negative impacts in their supply chains. Due diligence should be appropriate to a company’s circumstances and can be adapted to deal with the limitations of working with business relationships. On the other hand, this may leave norms open and companies have expressed a need for legal certainty in the case of a due diligence obligation. How can the dynamic nature of the OECD Guidelines be combined with more detailed legislation and a need for legal certainty?

Oversight and sanctions

A delicate balance must also be struck in the development of an oversight and sanction mechanism. Oversight should – in line with the international frameworks – be aimed at continuous improvement as reflected by the due diligence process, which has the goal of improving the situation in the value chain. Could the concept of dynamic supervision be an interesting idea? This type of supervision is based on stimulating companies to improve their game and focuses on best practices, while leaving room for sanctions.

Thus, there still remain some unresolved questions about the new Dutch RBC policy. What should be the scope for the broad due diligence obligation? How can flexibility be maintained in the law, while also giving businesses clarity and achieving positive impacts for rights-holders in the supply chain? And what systems of oversight are needed to both stimulate continual improvement and sanction non-compliance?

[1]: the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines)

(Photo: Eva Blue)

Leave A Comment