On November 17, OpenAI’s CEO Sam Altman was fired by the board of directors of OpenAI. Speculations about what happened suggest that there was a separation in the company between the commercially-minded Altman on the one side, and the more cautious non-executive board of directors on the other. The board fired Altman to slow down innovations in AI in order to be more careful about the dangers AI was creating for humanity. With this, the board was trying to protect OpenAI’s mission ‘to ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.’ After a great majority of OpenAI employees threatened to leave the company for Microsoft’s newly established AI team, Altman was reinstated as CEO and the board of directors was replaced by a more commercially-minded board.

Among countless reactions, Altman’s dismissal led some to argue that a crucial weakness in the governance of OpenAI was due to its non-profit structure. In fact, OpenAI has a type of steward ownership structure, in which control over the company is exercised by persons connected to the long-term purpose of the company. Ownership in this concept does not refer to ownership in a strictly legal sense, but in a more general way to the ultimate control over the enterprise.[1] Steward-owned companies have existed for many years around the world. Well-known examples include Novo Nordisk, Carlsberg, IKEA, and since 2022, Patagonia. Steward ownership as a concept was however introduced only a few years ago by the German Purpose Foundation. Especially in Northern Europe, steward ownership structures are now becoming increasingly popular as an alternative to mainstream shareholder-controlled company structures. Judging from the posts about OpenAI’s ‘unconventional structure’, in the US steward ownership is still a much more alien concept.[2] Quite ironically, the story is now being framed in a way that undermines the viability of this model, that seems ever more compelling as companies are trying to pursue all kinds of social purposes. Therefore, rather than concluding from the OpenAI story that companies cannot successfully be controlled by stewards instead of self-interested investors, this blogpost critically analyses the way in which steward ownership was implemented in OpenAI – and what other companies that want to become steward-owned can learn from this.

OpenAI’s steward ownership structure

In the most common company structures, executives are under the control of shareholders, who usually exercise this control in line with their financial interest in the company. This leads to incentives for executives to run the business in the most efficient way, in order to deliver solid (or even high) financial returns. The idea behind steward ownership structures is to ensure that executives prioritize the mission of the company by taking away incentives for profit maximization. Steward ownership is based on two principles. First, control is exercised by stewards: persons without economic interest in the company who control the company in line with its mission. And second, profits serve the mission and profit distributions to shareholders should be either excluded, if the principle is interpreted strictly, or capped, if the principle is interpreted so that profit distributions to non-controlling shareholders are possible as a ‘fair compensation’ for their investment.

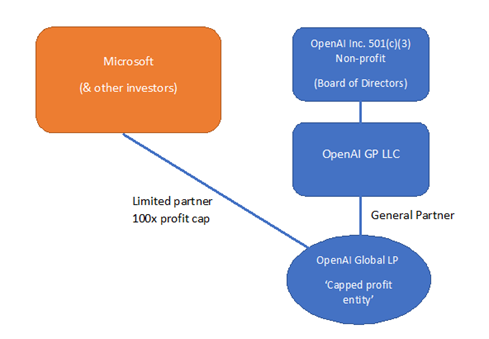

OpenAI’s structure more or less adheres to these two principles. A bit simplified, it comes down to the following. A not-for-profit entity (OpenAI Inc.) is on top of the structure. This not-for-profit entity is run by a board of directors. Through a limited liability company (OpenAI GP LLC), the not-for-profit entity is a ‘general partner’ in the for-profit subsidiary OpenAI Limited Partnership (OpenAI LP). The for-profit subsidiary was created in order to attract multiple investors including Microsoft. The investors have no controlling say in OpenAI and receive a capped dividend. The for-profit entity is thus governed by the board of directors of OpenAI Inc. The board of directors appoints their own members and is therefore the highest controlling body in the company.

On a sidenote: OpenAI’s structure is a bit of an unusual steward ownership structure, as stewards are mostly – in terms of corporate structure – on the shareholder level. Because OpenAI is structured as a limited partnership, it has no shareholders but partners. As a result of this structure, the board of directors is acting as steward in its capacity of general partner of OpenAI. As is common in US companies, this board of directors decides on the appointment and dismissal of the executive directors of the (for-profit) company, including CEO Altman. The board therefore has similar rights as shareholder-stewards would have.

Image: OpenAI’s company structure simplified. Source: openai.com/our-structure and https://fourweekmba.com/openai-organizational-structure/

In the following, the position of executives, stewards and investors in the OpenAI case is analysed in more detail in light of the two principles of steward ownership.

The position of stewards, executives and investors in OpenAI’s steward ownership structure

Steward ownership takes control away from persons with economic interest and therefore fundamentally changes the position of investors. In exchange, it creates the role of the ‘stewards’: persons who are ‘deeply connected to the operations or mission of a company’ – like the managers, employees, or industry leaders. Through this, it aims to transform the incentives for executives: instead of being focused on financial returns, executives should be focused on the mission of the company. When looking at the case of OpenAI, a first remarkable thing in this context is that the CEO was still prioritizing profit and the interest of investors above OpenAI’s mission – at least the board of directors thought so. One of the reasons for this could be Altman’s background: before founding OpenAI, he was the president of Y Combinator, a venture capital provider that has funded many Silicon Valley unicorns. In other words, he grew up with the profit maximization narrative. But next to his background, it is also very likely that pressure by Microsoft and other investors had something to do with Altman’s commercial mindset.

Let’s have a closer look at Microsoft’s position in OpenAI. Microsoft has invested computing power and cash in OpenAI with a value of around $11 billion. In return, Microsoft got 49% of the control in the for-profit entity, and an exclusive partnership, meaning that they had the exclusive right to commercialize OpenAI’s technologies in their own products and services. Moreover, Microsoft has a right to receive capped profit distributions. The cap is set at 100 times the investment. Excess returns above the cap would go to OpenAI Inc (the not-for-profit entity), that would use it for a range of charitable activities. However, before this happens, Microsoft can first receive up to $1.1 trillion in dividends from OpenAI. Here, the OpenAI case raises the question whether profit distribution should be at all possible within steward-owned enterprises and if yes, how high the profit cap can be. Namely, if the whole point of steward ownership is to ensure that decisions in the company are not made under the pressure of profit motives, then a possible dividend return of $1.1 trillion might be a bit dangerous. Because of this, the CEO was probably very much under pressure to keep this crucial investor happy. The OpenAI case thus shows that the behaviour of executives is not just steered by corporate incentives – but also by their background and more informal power relations.

If the stories are true, Altman was dismissed by the board of directors in part because of this commercial mindset. The board exercised their right to dismiss executives in order to slow down OpenAI’s technology innovations to make sure they were executed carefully. Therefore, the dismissal on itself can be seen as an example of the potential of steward ownership in protecting the company’s mission over profitability and growth. The way in which Altman was fired is however questionable: very abruptly, during a Friday afternoon video call, and without clear explanations given to him or to OpenAI’s stakeholders. If the board would have thought through the process better, the chaos that it resulted in could potentially have been avoided. What’s more, the non-executive board had slimmed down from 8 to 4 people and no one seems to know how they have been appointed. The board was thus not directly supported by stakeholders such as the employees and investors.

As a result of all this, the preliminary outcome of the whole drama is that Altman was reinstated as CEO and the board of directors was replaced. Here, it became again very clear that Microsoft had ways of exercising power over OpenAI even though it did not formally have the final say according to the corporate structures. Namely, all this happened under the pressure of Microsoft taking over all OpenAI’s employees. Eventually, Microsoft has even ended up on the board of directors of OpenAI – without formal say, but likely with even more informal power than it already had.

It is only to be seen what the change in board of directors will mean for the mission of OpenAI. According to the statement by the new board, the ‘governance structure’ of OpenAI will be ‘enhanced’. Although it is not entirely clear what this entails, the possibility at least exists that the steward ownership structure will lose much of its meaning. As far as we know, there is no security mechanism preventing the board from doing so.

Lessons for steward ownership

What can we learn from the case of OpenAI for other enterprises that want to implement steward ownership structures in order to be driven by purpose instead of by financial returns? The main message of the OpenAI case is that simply legally separating voting from profit rights is not sufficient. People’s behavior is not just steered by corporate structures and incentives, but for a large part by their background, organizational culture, and by more informal power structures. Steward ownership therefore needs serious checks and balances in order to secure the priority of the mission for the long term. In the case of OpenAI, the implementation of the structure was too fragile – especially for a company with such a big social impact.

On the basis of the OpenAI case, three points in the structure of steward ownership should be emphasized. First, it matters who are the stewards. The case of OpenAI shows that it is wise to think through a policy on the people who should act as stewards. Stewards would ideally be chosen from a diverse group of stakeholders, so that they have some support from within and outside the company.[3] Hence, not just Microsoft should get a place at the discussion table, but also other stakeholders such as e.g. an employee representative, a stakeholder representing humanity, and a stakeholder representing OpenAI’s customers. Second, it matters what happens with the profits. If profit distribution is allowed, profit caps should ensure that investors do not get too big of a stake in the enterprise. Third and finally, ‘security locks’ such as veto shares to enforce these principles are important. Steward ownership structures are often implemented in combination with veto shares held by an institution that only exercises the veto shares in case the steward ownership structure is endangered. In the case of OpenAI, the person holding this veto share could prevent that the steward ownership structure is abolished for e.g. a shareholder-ownership structure.

Although many companies with different varieties of steward ownership are flourishing, it is wise to be mindful of these points when setting up a steward ownership structure. This is important for any company that wants to make sure that purpose is put above profit – not just if their product can potentially extinguish humanity.

[1] The term is supposed to point out that the company is not controlled by ‘traditional’ shareholders or partners who exercise the control in their own interest, but by stewards that exercise the control in the interest of the company’s purpose. Although shareholders are often considered to ‘own’ the company, this is not legally correct. The same goes for stewards ‘owning’ the company.

[2] For a long time, enterprise foundation structures were not allowed under the 1969 Foundation law. Only recently, legal changes have created more space for enterprise foundation structures.

[3] Following the example of steward-owned companies in Europe such as book webshop YouBeDo (https://www.youbedo.com/)

(Photo: Growtika)