Amsterdam’s vision of becoming a sustainable city

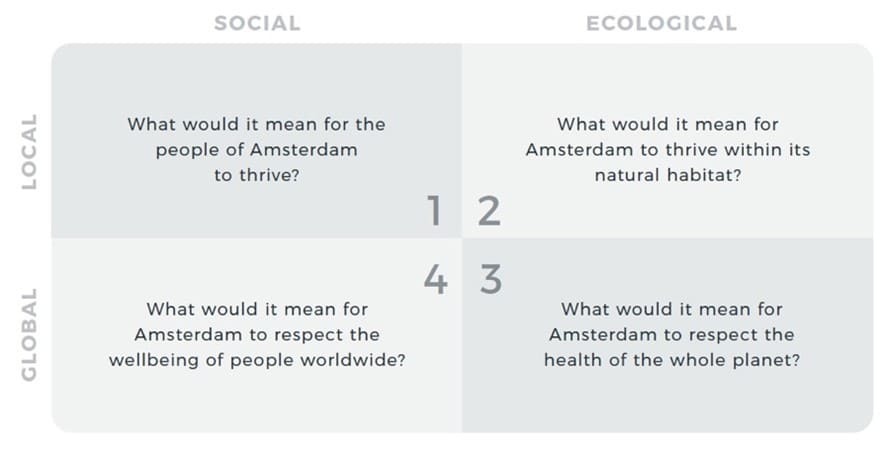

We have been fascinated by two small bottom-up initiatives in and around Amsterdam: the Community Land Trust in Amsterdam South-East and the so-called Zoöp. In a recent article, we analyse the potential and the limitations of these two bottom-up legal innovations to assess how they could help the city of Amsterdam meet its ambition to transition to a doughnut-proof economy, based on Kate Raworth’s ‘doughnut economics’. A doughnut-proof city meets the needs of its people and the local natural habitat, while respecting the well-being of people globally (‘social foundation’) and staying within planetary boundaries. Together with Raworth, municipal officials made a ‘city doughnut’ with four key questions that should guide Amsterdam’s transition towards sustainability:

Amsterdam City Doughnut, by Kate Raworth

In our analysis, we have paid particular attention to what these innovations do to our understanding of private law categories and how they use conventional private legal tools to alter whose voices get heard and whose interests count in our economic and political system. The CLT and Zoöp models demonstrate that the legal modules of property and representation indeed can be adjusted such that the legal system can better accommodate an economic system in which neither planetary boundaries nor social foundations are transgressed. Importantly, they are able to do so by utilizing private legal tools of company law, corporate governance and contract law without having to wait for governmental institutions to adopt legal reform.

The Community Land Trust

For the past 50 years, the Bijlmer in Amsterdam South-East has been perceived as the roughest part of Amsterdam. By the end of the 1980s, the area had the profile of a poor neighbourhood, with soaring crime rates, drug abuse and unemployment. In 1992, the municipality of Amsterdam, the city council of South East and the social housing corporations decided for a large-scale area renewal. ‘However, residents continue to struggle, to fully prosper socially and economically’, Moses Alagbe – Initiator and Board Member of the CLT H-neighbourhood – notes, which he states can be explained by high costs of living and disappearance and lack of physical community infrastructure to support emancipation, community activities and capacity building.

A grassroots organisation that has been active in the H-neighbourhood in the Bijlmer for more than 15 years, initiated plans to contribute to the development of their own neighbourhood through a Community Land Trust (CLT). Community members set up an open member association called CLT H-neighbourhood that consists of a diverse community with over 180 members. The group chose community development first, including the establishment of the association, even before a concrete plot of land was available to them. The community uses the CLT model, which finds its origins in the US from 1969 onwards. Central to any CLT are: self-organisation, shared ownership and real estate management and operation. The CLT H-neighbourhood hopes to attain land to develop the neighbourhood, based on five guiding principles:

- affordability in the present, for current residents from low- and middle-income population group;

- affordability in the future by making speculation with housing or rapid rent increases impossible;

- connectedness with the neighbourhood through permanent decision-making power of local residents over developments in the vicinity of their homes and neighbourhood facilities;

- stimulating self-reliance and providing opportunities for the socioeconomic emancipation of residents from the neighbourhood, by having them take charge of the elaboration and organization of the projects; and

- combining the development of the CLT model with circular area development.

In traditional area development processes, urban sites are usually maximised for economic return. The CLT demonstrates that property rights might just as well be used to protect collective use rights and sustainable practices. It shows that the legal module of ‘property’ can be imbued with new meanings to better accommodate an economic system in which neither planetary boundaries nor social foundations are transgressed. The community is able to do so by utilizing existing legal tools of company law and contract law without having to wait for governmental institutions to adopt legal reform.

Nevertheless, the CLT initiative in the H-neighbourhood makes clear how important the support of local government is for communities to participate in remaking the city. While the CLT H-neighbourhood has been building their community from 2018 onward, the municipality keeps postponing the tender for the actual land on which the community hopes to build its houses and neighbourhood facilities. It is not unlikely that that tender will come out six years after the CLT H-neighbourhood started their efforts. It is difficult for the CLT to keep people engaged if there is no clear plan that they will be able to remake their neighbourhood. Moreover, due to electoral cycles, the people with whom they engage at the municipality come and go and the community must start from the scratch, engaging with the municipality over and over again.

In its vision for 2050, the Amsterdam municipality expresses its support for bottom-up initiatives, including the CLT H-neighbourhood. It is yet to be seen whether this is mere lip service. The support required is not merely about making available plots of land for CLTs; what is critical here is the recognition and understanding that law and regulation frequently operate as barriers to community engagement in remaking the city and accordingly build the design to circumvent such barriers. The process of taking ownership for their neighbourhood is at times such an uphill battle that disincentivised people to develop feelings of ownership of their neighbourhood or their city. Municipalities must learn from this experience and assist people hands-on in taking responsibility for shaping their neighbourhoods in a collaborative manner.

The Zoöp

The Zoöp is an organisation model that makes sure that there is a person on the board of any organisation whose only task it is to represent non-humans, like animals, plants, and ecosystems. The Zoöp was launched in 2022 and developed by the Rotterdam-based museum Het Nieuwe Instituut (The New Institute), supported pro bono by lawyers from Amsterdam law firm De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek. What is unique about the Zoöp is how it radically changes whose voices are represented in organisational decision-making: Zoöp is not only about realising environmental standards; the model also enables deliberating with the nonhuman world on what those standards should be.

This is how it works in a nutshell: There is a so-called Zoönomic Foundation, that employs ‘speakers for the living’: human experts in regeneration who can voice the nonhuman interests in the executive board of any organisation that wants to be a zoöp. To become a zoöp, an organisation must also subscribe to a ‘Zoöp Manifesto’ and make it easily accessible on its website. Once these conditions are met, the Zoönomic Institute will license the organisation as a zoöp. The newly established zoöp commits to carry out a baseline assessment, mapping the ecological system within its domain. Thereafter, the zoöp sets out yearly goals for ecological regeneration. In this way, the zoöp ensures to operate in harmony with nature.

There are already organisations inside and outside Amsterdam that adopted the Zoöp model, including the art platform and community garden called Zone2Source, the future hotel Fort Abcoude and the holiday resort Sumowala. As this model is relatively new, it needs to be awaited how it will work out in practice. What can already be said though, is that the Zoöp model builds on the claim that nature has intrinsic value and therefore merits institutionalised representation, and that such representation will lead to better environmental protection, at least within the premises of a Zoöp organisation. By doing so, the Zoöp model imbues the legal module of ‘representation’ with new meanings to better accommodate an economic system in which neither planetary boundaries nor social foundations are transgressed. Non-humans are no longer (only) at the menu, they are at the table in zoöp organisations. The Zoöp is able to achieve this by utilizing existing legal tools of company law, corporate governance and contract law without having to wait for governmental institutions to adopt legal reform.

The municipality of Amsterdam could enhance the sphere of influence of this private initiative by either recognizing the rights of the local environment or restructuring some of its key agencies into zoöps in which nonhuman interests (and, by extension, the interests of people elsewhere) are represented. Hence, if the municipality of Amsterdam takes its own Doughnut Strategy seriously, it ought to recognise the innovative changes made by private parties, support them and spread their insights. That way, the city can also inspire those beyond its boundaries to adopt an ecologically sustainable and socially just way of living.

How CLT and Zoöp help Amsterdam become doughnut-proof

The CLT and Zoöp demonstrate that through committed action on the basis of alternative interpretations, one can remake legal meaning, imbue property relationships with place-based responsibilities and feelings of belonging, and incorporate ecology in models of representation. Hence, our analysis confirms that meanings of legal structures such as property and representation depend upon their social, material and temporal contexts that are not fixed but rather to be negotiated over time.

The CLT empowers local people, whereas the Zoöp empowers local ecology. But neither of the initiatives does everything at once as envisioned by the Doughnut-model: take good care of local people and people elsewhere and the local environment and the planet. To remedy this, there is room for cross-fertilization between the CLT and Zoöp. The Zoöp can lend its expertise to build in representation for the local natural habitat and the planet in the governance design of the CLT. The CLT’s expertise on the use of ownership to nurture a sense of stewardship for inclusive and empowered local communities can inspire the designers of the Zoöp model to maximize its potential for social inclusion. Moreover, both models would benefit from exploring how people elsewhere could be represented in their governance designs, inspired by the way in which zoöps enable representation of voiceless nonhuman actors already now.

While the CLT and Zoöp models can be enhanced to optimally contribute to Amsterdam’s transition towards sustainability, our analysis results in the empowering message that people can utilize the already existing private legal tools of company law, corporate governance and contract law to remake their city without having to wait for governmental institutions to adopt legal reform.

However, the CLT and Zoöp demonstrate the fundamental importance of legal, municipal and other expert support to make legal innovation in service of a sustainable city happen. The development of the Zoöp model was supported pro bono by lawyers from De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek. The CLT H-neighbourhood is constantly supported by a coalition of experts from the advisory firm – And The People; the advisory firm – Common City; housing-related advisory services provider – !Woon; and the design studio – Space&Matter. This coalition of experts assist the community with the engagement with local government and working through the legal and regulatory complexities of making a CLT initiative come to life.

A lack of understanding of relevant processes, or even an absence of such processes, can make it very difficult for community members to participate in remaking the city in more socially just and ecologically sustainable ways. Thus to all lawyers, civil servants and other relevant experts out there, we invite you to lend your hand and enable the bottom-up changemakers in our cities to imbue the notions of property and ownership with new meanings in service of the transition towards sustainable cities.

Interested to read more? Have a look at: www.erasmuslawreview.nl/tijdschrift/ELR/2022/3%20(incomplete)/ELR-D-22-00036

<small>(Photo: <a href=”https://pixabay.com/nl/photos/amsterdam-kanaal-storm-stad-lucht-1910176/”>user32212</a>)</small>